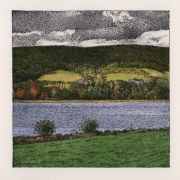

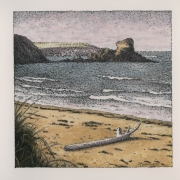

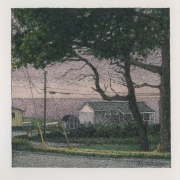

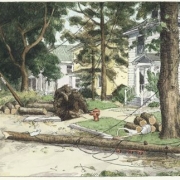

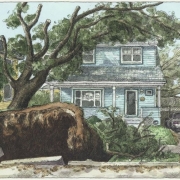

This showing of 45 original drawings and watercolours by Paul Hannon was held at the Chase Gallery, Nova Scotia Archives, 6016 University Ave. Halifax NS. Dec. 5, 2019 – Jan 30, 2020. Paul created 16 new works on paper for the show including new images of Cape Breton & Halifax. These are done in a very media-specific method using pencil, pen and watercolour worked to a surface resembling printmaking effects. The Hurricane Juan Series from 2003 consisting of 13 larger works as well as his ancestor series of imagined family tree members (12 works) and several pen drawings.

Introduction to “Selected Drawings” by Mollie Cronin

Like Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawks” (1942), Hannon’s portraits of the urban witching hour capture a kind of eerie quiet, the peaceful stillness of the night and the uneasiness of the dark. With any painter who is able to capture their subject with convincing and enticing realism, as Hannon does so successfully, there is always the curiosity as to just how such a thing gets made. In Selected Works Hannon gives us a glimpse into his detailed practice, revealing drawings that are every bit as polished and engaging as his oil paintings. Pulled from the last 25 years, Selected Works boasts Hannon’s familiar night scenes, as well as coastal landscapes, figurative work, and historic images that confirm Hannon not just as a talented painter but as a skilled image maker. (continued below)

(continued from above)

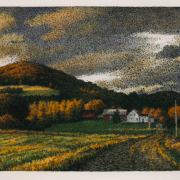

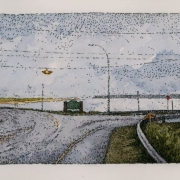

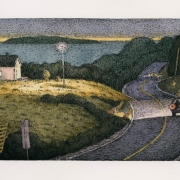

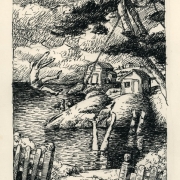

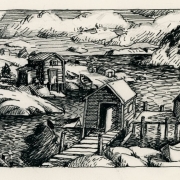

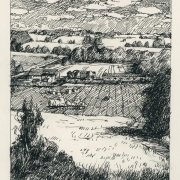

In his recent drawings of Halifax and Cape Breton, the black marks that Hannon has layered over watercolour are almost pointillistic in their congregation. The small black ink work builds to consume dark corners and alleys, dense foliage, and heavy banks of cloud. Here Hannon’s training as a printmaker is evident: the careful layering of colour superimposed with these deliberate marks feels in keeping with how layers of coloured ink and carved, black lines would be arranged in a print. It is a technique that demonstrates the amount of thought, time, and labour that goes into these drawings.

Halifax is a city that never sleeps – or at least it certainly feels that way to any of us living near its main thorough fares. With its glaring lights announcing pizza and donair, fluorescent lit corner stores, and traffic lights trying their best to cut through the fog, Halifax has a nocturnal colour palette all its own, one that time and time again is expertly captured in the paintings of Paul Hannon.

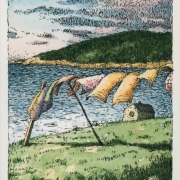

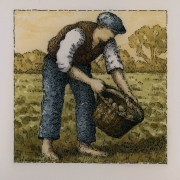

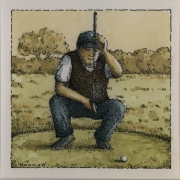

Labour is thread that connects many works in this exhibition. Drawing from the paintings of Jean-François Millet, Hannon has imagined portraits of his ancestors based on what little details he knew of them: their occupation and the kind of dress common in those eras. The figures in the resulting Workers series show labourers in the process of farming flax and potatoes, of women laundering, as well as more contemporary labour like a worker on a golf course. Many of these scenes could be easily at home in Inverness, Cape Breton, where Hannon and his wife own a home and are active in the local arts scene. The golfer seems to have stepped off of the Cabot Links, while the line of laundry drying against the Atlantic coast feels timeless.

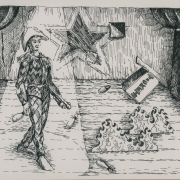

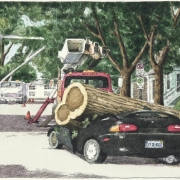

In the Medieval and Early Renaissance periods artists would depict the Labours of the Months as twelve distinct scenes: often rendered in stained glass, these twelve images would depict agrarian labour typically performed in each month (shearing of the sheep, butchering of the hogs, cutting flax, etc.). It was a theme visited by master realist Alex Colville in the 1970s, when he created a suite of prints under the name “The Books of Hours, Labours of the Months” (1978) featuring quintessentially Colvillean moody portraits of figures throughout the seasons. In this exhibition Hannon has managed to amass his own Labours of the Months: from farm work, to seasonal labour in Cape Breton’s tourism industry, to the construction teams removing Hurricane Juan’s debris from the streets of Halifax, Hannon’s drawings of Nova Scotia as he sees it and the past as he imagines it show a keen eye for this place, it’s industries, and the role of the artist in capturing such things. In addition, the influence of Colville is glaringly present in works such as “In a Dark Four Door” (2019), showing an abandoned car perched on the edge of a cliff, like many of Colville’s paintings that feature observers on the precipice. But in the end it is Hannon himself who becomes this observer, standing and drawing amongst fallen trees and telephone wires in 2003, or perhaps on the edge of a dark, curving Cape Breton highway in the present day. He is carefully and keenly situated: the artist seeing all and graciously and masterfully mirroring it back to us.